Our next glimpse of Fowler comes only with his first copyright registration; on February 13, 1919 a lead sheet for "Before Day Blues" with words and music by Lemuel Fowler was deposited at the Library of Congress, along with copyright depositions for two other compositions from the same publisher, Griffin Music of Chicago. Fowler had joined the Great Migration of African-Americans from the Deep South to northern urban areas around the end of the US participation in WWI and had moved to Chicago.

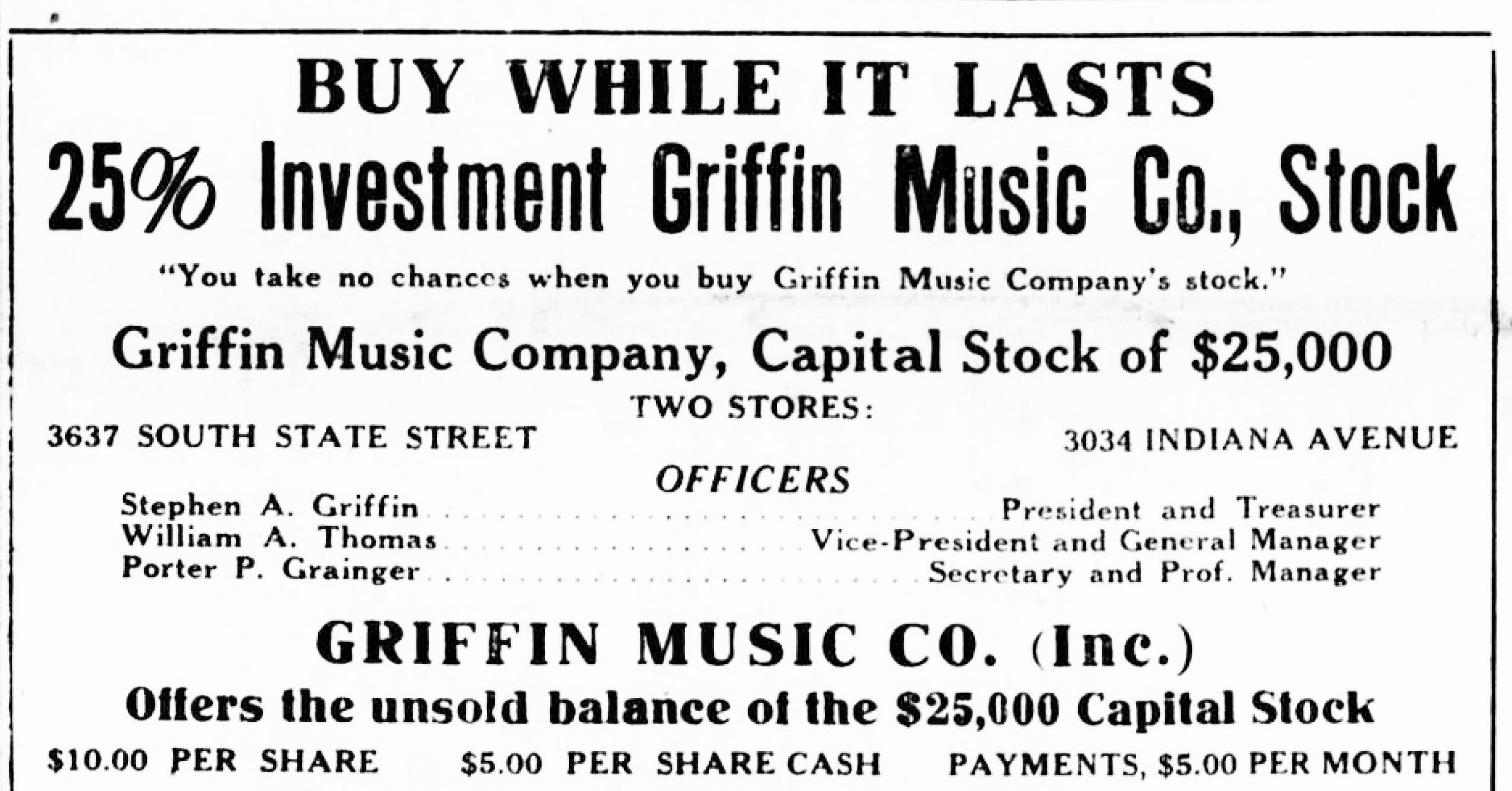

Griffin Music had been founded in 1916 as Griffin Music House, a music store at 3637 South State Street in the heart of "The Stroll" (South State Street from 31st to 39th), which was the famous center of African-American life in the 1910s and 1920s on the South Side of Chicago. The firm dipped their toes into the waters of music publishing in 1917, purchasing Maceo Pinkard's (1897-1962) "Those Draftin' Blues" and publishing it that year, evidently with some success, judging by the number of recordings made of the tune. Griffin published another song, "You Lied", by J. Russel Robinson (1892-1963), Marguerite Kendall (1891-1921) and Spencer Williams (1886?-1965), in May 1918, and copyrighted two more tunes late in the year. By late 1919, Griffin had decided to go into music publishing more seriously and published a solicitation to sell stock in Griffin Music Co. in the African-American newspaper "The Chicago Whip" (December 19, 1919). The advertisement lists the personnel: Stephen A. Griffin, president, William A. Thomas, VP and general manager, and Porter P. Grainger (1891-1948), the songwriter, as secretary and professional manager.

Upper part of stock solicitation ad in Chicago Whip, Dec. 19, 1919.

Lem Fowler's first copyrighted composition that Griffin registered on Feb. 13, in the name of their general manager William A. Thomas was a straightforward 12-bar blues; both the verse and chorus are in that form. The copyright registration lists the arranger of the tune as Clarence M. Jones, a central figure in Chicago pop music in this period. Jones arranged the unpublished copyright "Will You Love Me While I'm Gone" by Frederick Johnson the previous year as well as "Thanatopsis Blues" by Griffin's staff man Porter Grainger, also copyrighted on Feb. 13. It is not clear what an arranger's contribution would be to a simple lead sheet when the composer is capable of notating music, and certainly Grainger was fully capable of notating his own work. Fowler, too, evidently was already similarly competent, as we learn from his next copyrighted composition. But Clarence M. Jones's arranging credit does raise the possibility that Jones had taught Fowler when the latter had arrived in Chicago, as Jones had taught James Blythe at around the same time. Otherwise, to date we have no information or even speculation about Fowler's musical education. Perhaps the "arranged by Clarence M. Jones" credit is something analogous to the "arranged by Scott Joplin" credit on the cover of Joseph F. Lamb's first Stark publication, "Sensation". In that case we have Lamb's first-person testimony that it was Joplin's idea to put that credit on the cover to improve the commercial prospects of an unknown composer like Lamb and that in fact Joplin had had nothing to do with the arrangement. And earlier in Joplin's career, the "arranged by Charles N. Daniels" credit on Joplin's first published rag, "Original Rags" was possibly something similar, though testimony from Daniels's son indicated that in that case, Daniels had really done arranging work on the piece ["King of Ragtime", Edward A. Berlin, (2nd edition), Oxford U. Press, 2016, pp. 60-62, p. 227]. |

1919 copyright deposition smaller.jpg) |

(1919) cover from L of C.jpg)

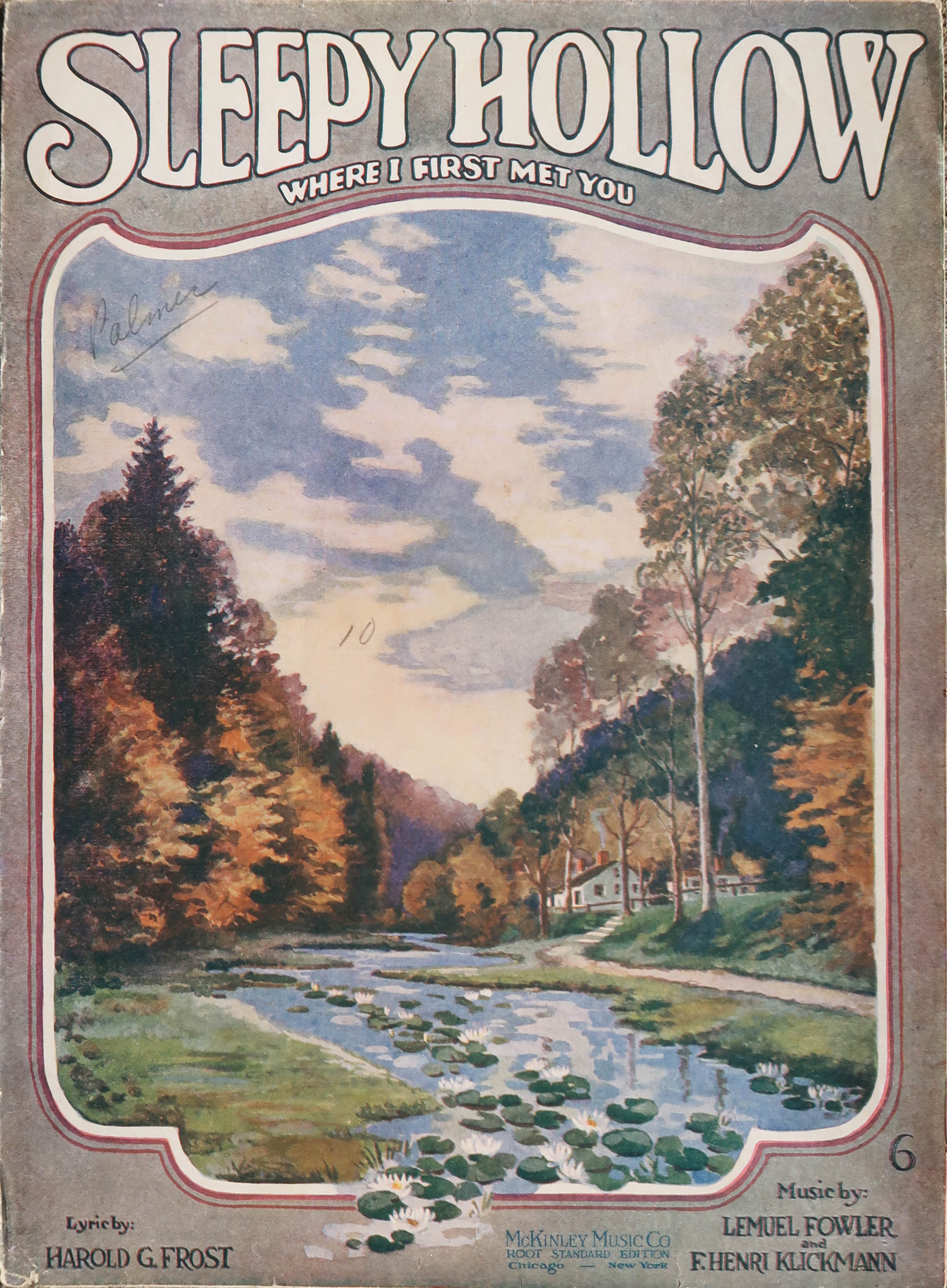

Fowler's next publication was a genre completely unique in his work - "Sleepy Hollow (Where I First Met You)", a waltz song with lyrics by Harold G. Frost and the music by Fowler and the veteran composer and arranger in Chicago, F. Henri Klickmann (1885-1966). The tune was first copyrighted as an unpublished work on July 12, 1920 and published by McKinley Music on November 5 of that year. One might speculate on how the composition credit came to be split between the 21-year-old relative neophyte from Alabama and the pillar of the staff of McKinley Music, a native of Chicago who was 13 years older than Lemuel. Perhaps Fowler created a melody and submitted it to McKinley Music, and Klickmann realized it might make a good waltz song and composed a verse. The chorus of Klickmann's hit waltz song "Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight" from 1918 (originally an instrumental entitled "Hawaiian Moonlight" copyrighted in 1917) features an identical rhythmic pattern and the heavy use of parallel thirds in the arrangements makes the two waltzes sound almost as though "Sleepy Hollow" is a sequel to "Sweet Hawaiian Moonlight". To convert the waltz tunes to songs, in both cases the veteran Harold G. Frost contributed a lyric. "Sleepy Hollow" was evidently a popular success, judging from the relative ease of finding copies of the sheet music today, and from the fact that most of the piano roll companies issued rolls of the tune, including Imperial (played by Gurnell Anderson 'assisted by R.H.' on Imperial 91254, issued in January 1921), Vocalstyle (played by Mary Allison and Walter Davidson on 11846) and Pianostyle as an instrumental 47753 and as a word roll on 11014. Strangely, the largest roll company, QRS, did not issue a roll of the tune, based on searches of their advertising and their catalogs.

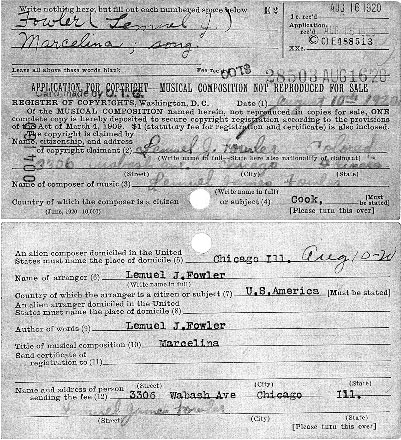

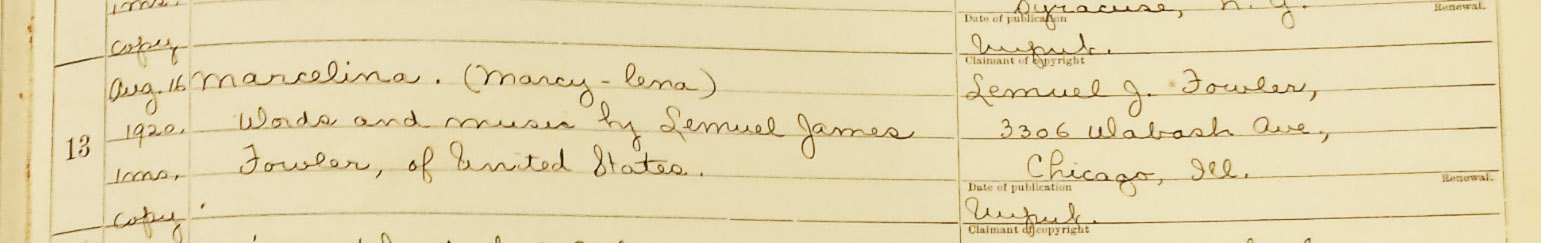

Fowler's next copyright marked a new advance for him, although it was never published. "Marcelina: A Blues Intermezzo" was deposited for copyright on August 16, 1920 by Lemuel James Fowler, as he proudly signed on both the front and the back of the card. One of the most significant aspects of this copyright registration from a biographical point of view is that it is the only source of a home address for Fowler in Chicago - the certificate of copyright is to be mailed to 3306 Wabash Avenue.

Here, too, we have three specimens of Lemuel J. Fowler's signature in 1920, to be compared to later examples.

Entry in the Copyright Ledger for Fowler's unpublished composition "Marcelina", for which the information was copied from the application that became the catalog card shown above.

The manuscript of "Marcelina" runs to over 5 pages, because the song is written on three staves, one for the vocal line and the other two for the fully scored piano accompaniment, and also because there is a third part to the song, marked "Trio", after the introduction, verse and chorus. At the end, Fowler notes that he arranged the song as well as composing it and writing the lyric, which is also noted explicitly on the back of the application card. At the upper right-hand corner of the first page, Fowler writes 'words & music by Lemuel J. Fowler, writer of the "Before Day Blues"[,]"I'm on my last go round"[, and ] "Sleepy Hollow waltz["]'. We do not know "I'm on my last go round". The manuscript looks as though it was intended to go directly to the engraver, though the style of notation changes noticeably after the first two pages to a somewhat less finished or less professional appearance for the remainder.

The riff in the 6-bar introduction is very distinctive, and Fowler would use it again in later pieces. The verse is essentially identical in its basic idea to the much-later verse of Clarence Williams's "Organ Grinder Blues", particularly to the piano solo version Williams recorded on Okeh 8604 on July 2, 1928. It would seem unlikely that Williams would have lifted this idea, complete with its rolling "Western" bass figuration, from Fowler's unpublished manuscript from eight years earlier, and more likely that this strain was something that was floating around among pianists in Chicago around 1920 that both Fowler and Williams picked up. In any case, Fowler's notation of that left-hand figure may be the earliest notation of that boogie-ish style. The melody of the chorus was recycled by Fowler in a slightly modified form as the verse in his 1923 tune "Squawkin' the Blues" (with a completely different lyric). Perhaps the most intriguing mystery of "Marcelina" surrounds the "trio" section. After a 4-bar modulating introduction, a sixteen-bar riff melody accompanied with a walking bass is presented and repeated once. This section is virtually identical to a 16-bar instrumental interlude (what piano roll collectors sometimes refer to as a 'solo verse') in Clarence Jones's Imperial roll (no. 9909) of "Just Blue", a composition by saxophonist F. Wheeler Wadsworth and Victor Arden (pseudonym of Lewis J. Fuiks) that was copyrighted and published in September 1918. Jones's roll was released in October 1919, ten and a half months earlier than Fowler's "Marcelina" copyright deposit. The roll interlude and the trio of "Marcelina" are even in the same key of B flat. Is this another indication of a teacher-student relationship between Jones (1889-1949) and Fowler?

The mystery of this trio section is deeper still - the tune is very much the same as the famous Spencer Williams tune "Basin Street Blues", which Williams copyrighted as an unpublished instrumental, without the later-added verse or any lyric, on November 12, 1928! Was this melody also a floating strain known around Chicago in the late 'teens? It is certain that Spencer Williams did something similar on several occasions, where he wrote down and copyrighted a melody that seemed to be floating around with nobody certain of who had originated it. For example, Spencer Williams copyrighted "Daigah's Dream (Brazilian Intermezzo)" in Chicago in 1919, where it was published only as an orchestration (not as a piano solo) by the small firm of C.A. Grimm. Upon inspection of this published orchestration, it becomes clear that this piece is a version of the notorious tango "The Dream", also known as "The Bull Dyke's Dream" or "The Diggah's Dream", etc., best remembered from the recorded versions made by Eubie Blake as "The Dream Rag" and James P. Johnson ("The Dream"). Another example from the same year of 1919 was "Trix Ain't Walkin' No More", which Spencer Williams and the unrelated Clarence Williams wrote down a floating strain and came up with a less rude lyric to fit it, copyrighted as an unpublished work June 26, 1919. This kind of thing is also reminiscent of James P. Johnson's story of his "Mama's Blues" of 1917, about which Johnson said "There had been a piece around at the time called "Left Her On the Railroad Track" or "Baby, Get That Towel Wet". All pianists knew it and could play variations on it. It was a sporting-house favorite. I took one opening strain and did a paraphrase from this and used it in 'Mamma's and Pappa's Blues'. It was also developed later into 'Crazy Blues', by Perry Bradford." (The Jazz Review, vol. 2, number 6; July 1959, p. 13.)

The address of Fowler's we learn from the "Marcelina" copyright registration card, 3306 Wabash Avenue, was just around the corner from "The Stroll" on State Street, in the heart of the African-American district after WWI. The entire block was razed when the Armour Institute of Technology expanded in the 1940s to become the Illinois Institute of Technology and is now on the site of a parking lot for an institute building. I have been able to locate the residents of that address in the 1920 census, enumerated on January 2, 1920, and unfortunately, Fowler is not among them, nine months before he had the copyright certificate sent to him at that address. In January, the residence is headed by Robert E. Gans and his wife Emma. They have eight roomers: Clyde Thomas and his wife Alberta, Dias Russel, Lee Johnson, a young widow at 27 named Cassie Murray and her son, who is twelve, Edward Simmons, and most remarkably, "Joe Mendez" who appears to be the baseball Hall of Fame player Jose Mendez. Mendez lists his occupation and employer as baseball player for the [Chicago] American Giants, a leading Negro League team. Though apparently Mendez did play for the team in 1918, in the 1919 season he played with Detroit, and he is listed as playing for the Kansas City Monarchs in the 1920 season and in fact managed the team in that season. Perhaps in January he had not yet signed with Kansas City and was hoping to return to the American Giants for the 1920 season. In fact, it was one month later that the manager of the American Giants, Rube Foster, led the organization of the Negro National League. We would like to imagine that perhaps when Mendez left the rooming house on Wabash to move to Kansas City to take up the managerial reins of the Monarchs, Fowler might have taken his room!

The fact that Fowler had evidently not moved into the rooming house at 3306 Wabash in January and has not been located in the 1920 federal census at any address starts a string of at least three censuses in which he has not (yet) been found (the 1950 census will become public in 2022).

The next-copyrighted work of Fowler's while he lived in Chicago seems to have been the only known case in which Fowler did arranging work for someone else. Fowler is listed as the arranger of a song entitled "Take It Daddy, It's All Yours" by Ernest S. Sweat (1890-1946), registered as an unpublished work January 3, 1921. Sweat's address, written at the bottom of the copyright deposition, of 3232 S. State Street (in the heart of The Stroll) matches with the 1920 census enumeration of January 8, 1920, which shows Sweat and his wife Beulah, and two children, as head of a household with five lodgers, including another married couple and their infant. It shows Sweat was a railroad porter. Evidently he had at least one song in him; Fowler lived only a block away at 3306 Wabash, so perhaps they were friends.

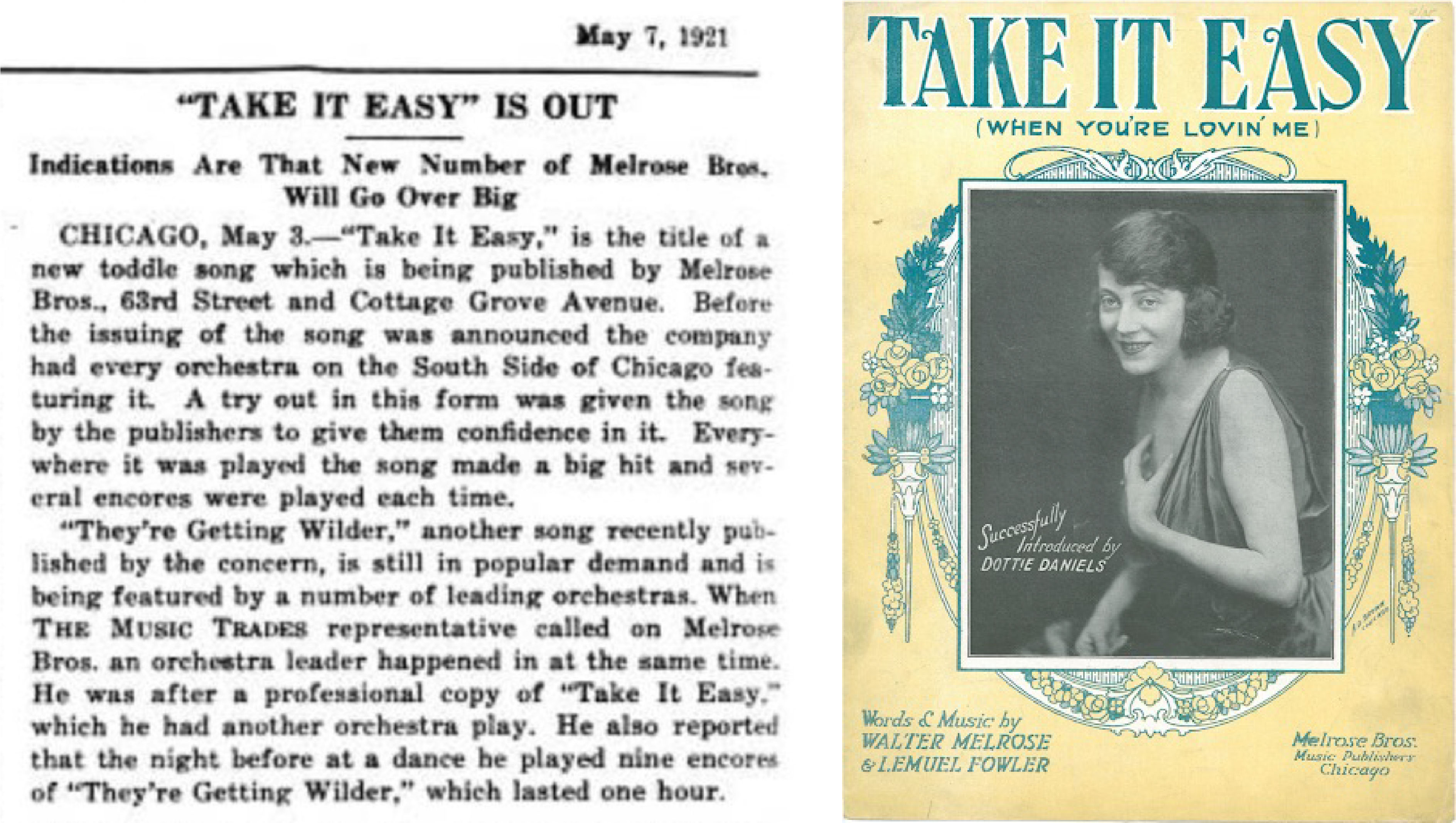

The final copyrighted work of Fowler's Chicago sojourn was published and aggressively plugged. Fowler sold "Take It Easy (When You're Lovin' Me)" to the Melrose Brothers, Walter and Lester, who copyrighted the tune as an unpublished work composed by Walter Melrose and Lemuel Fowler with lyrics by Walter on April 18, 1921 in an arrangement by Harry Alford. We can be fairly sure that Walter had nothing to contribute to the music, and quite possibly had little to do with the lyric, but that Melrose 'cut himself in' on these credits to increase the fraction of the profit that would be due to him, a typical pattern of behavior for a small publisher that was not too troubled by ethics at the time. The Melrose Brothers later were very successful in dealing with Jelly Roll Morton and other African-American composers a few years later, often employing similar tactics to maximize their profits. Although the only copyright deposition is of the unpublished version of the tune, Melrose Bros. did publish the tune without bothering to register the published version, as seems to have happened frequently in this period. Melrose did manage to have it played in a concert of tunes controlled by his firm over station KYW Chicago on May 5, 1922, in which it was played by "Hofferan's Society Orchestra". Melrose also arranged for a plug for "Take It Easy" to appear in "The Music Trades" on May 7, 1921 (p. 54). Despite these marketing efforts, the sheet music of "Take It Easy" is very rare, with one copy in Richard Riley's comprehensive collection, so that it cannot have been very popular.