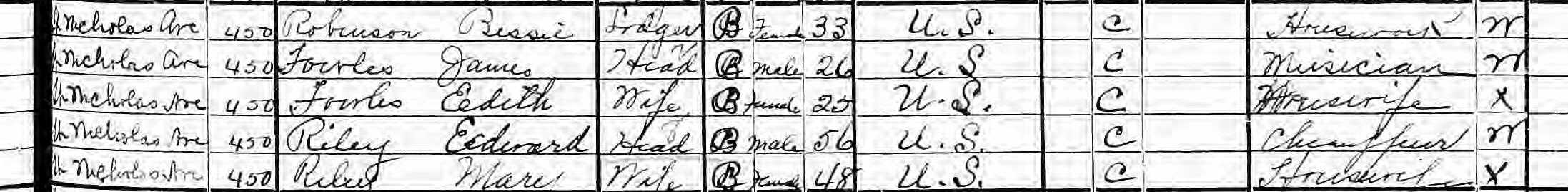

James and Edith Fowler listed in the 1925 N.Y. State Census, residing at 450 St. Nicholas Avenue, the address which Fowler used on his copyrights for the remainder of the 1920s. No evidence that Fowler and Edith Smith were actually married has been located to date. Lemuel and Edith are two of 122 residents of the apartment building at that address enumerated in the census.

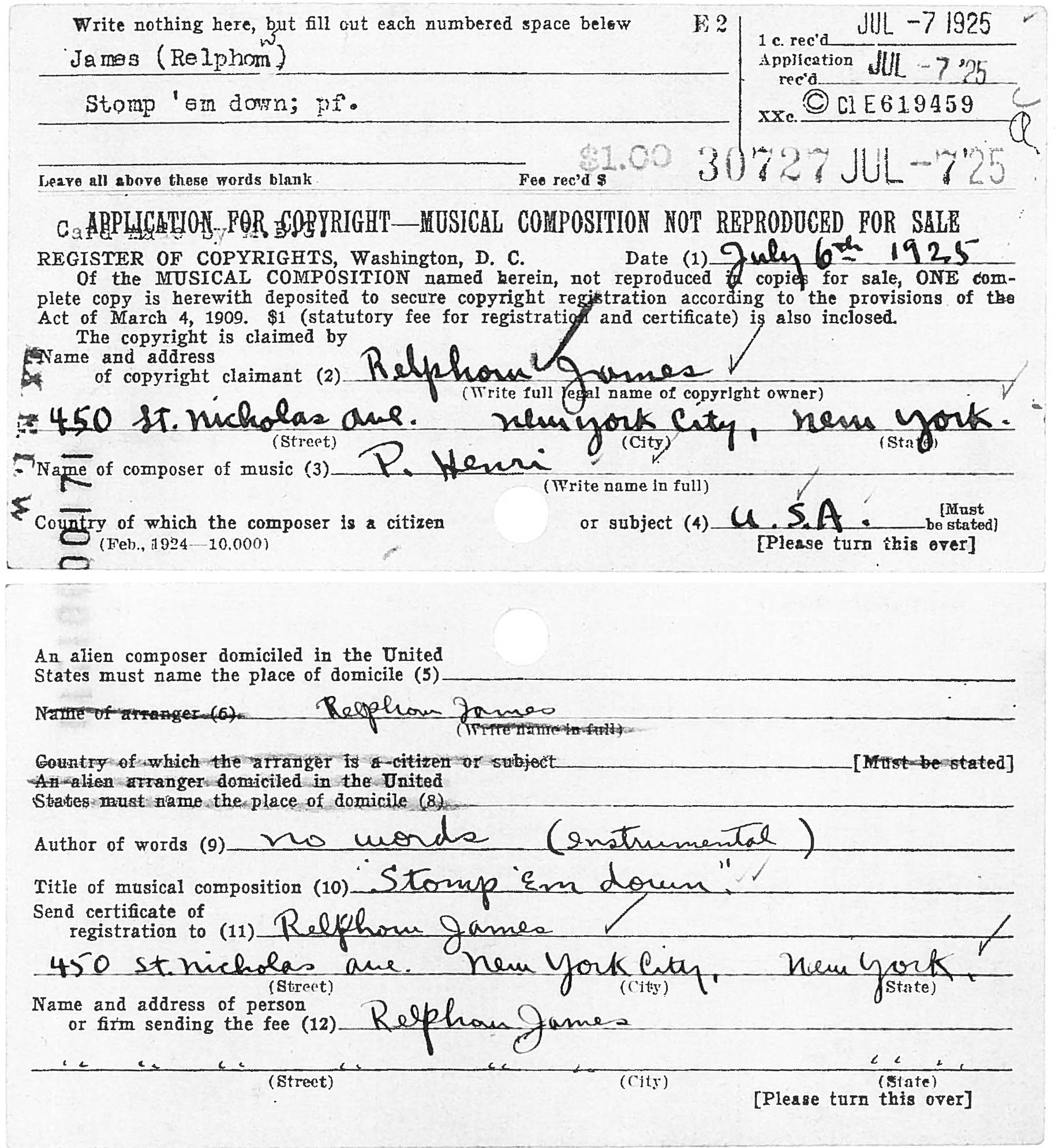

Copyright application for "Stomp 'Em Down" by 'P. Henri', arranged by 'Relphow James', residing at 450 St. Nicholas Avenue in 1925.

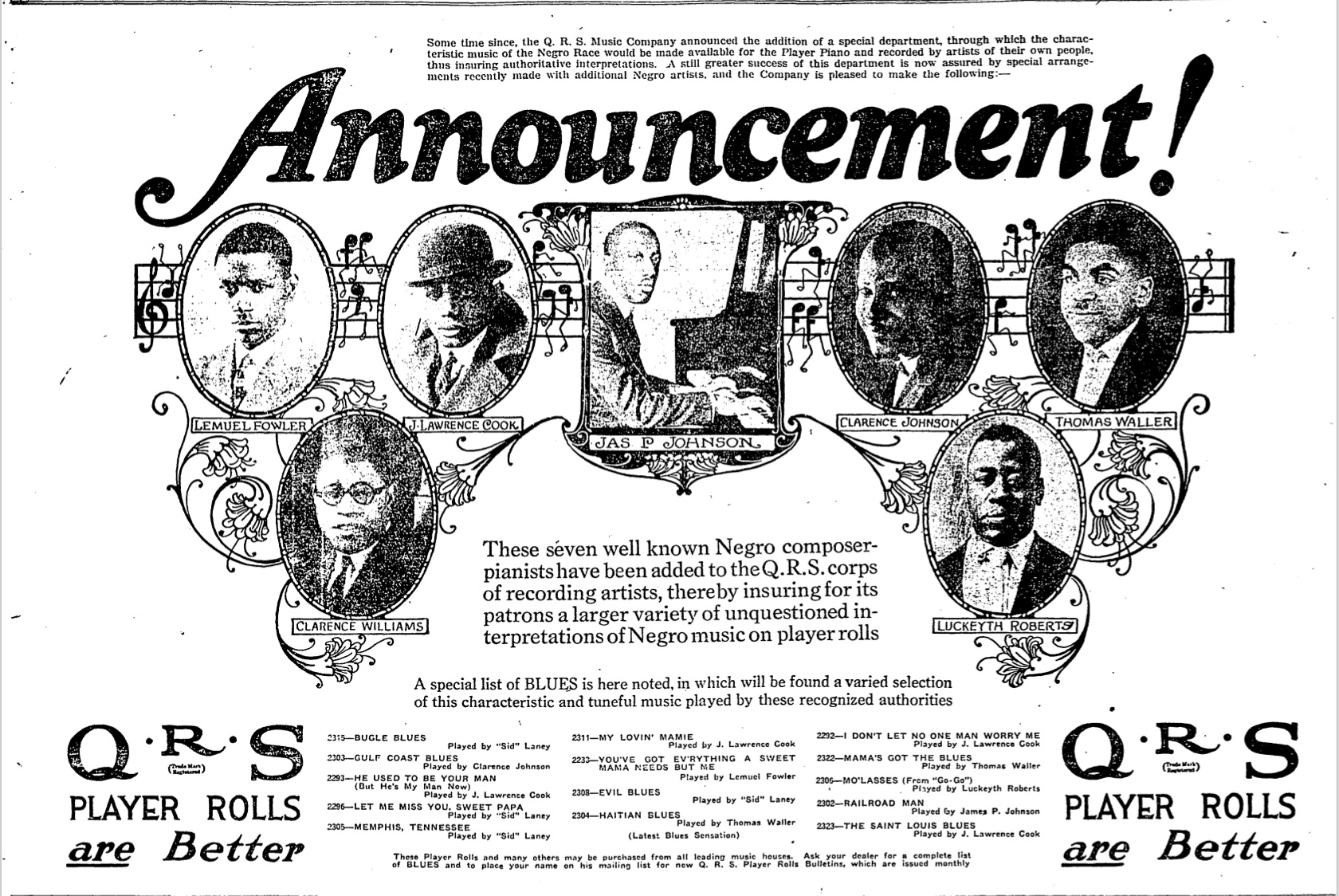

From the Pittsburgh Courier, regarding Fowler making rolls for QRS. At left, from September 8, 1923, page 11, and the clipping at the right, July 14, 1923, responding to QRS issuing the "special blues bulletin" of July 1923, advertised in the African-American newspapers that summer.

The well-known QRS display ad from the Chicago Defender, August 18, 1923, p. 6, showing a crop of Fowler's QRS headshot, and the James P. Johnson QRS shot from 1921, along with a very early photo of Fats Waller, and a photo of Clarence Johnson.

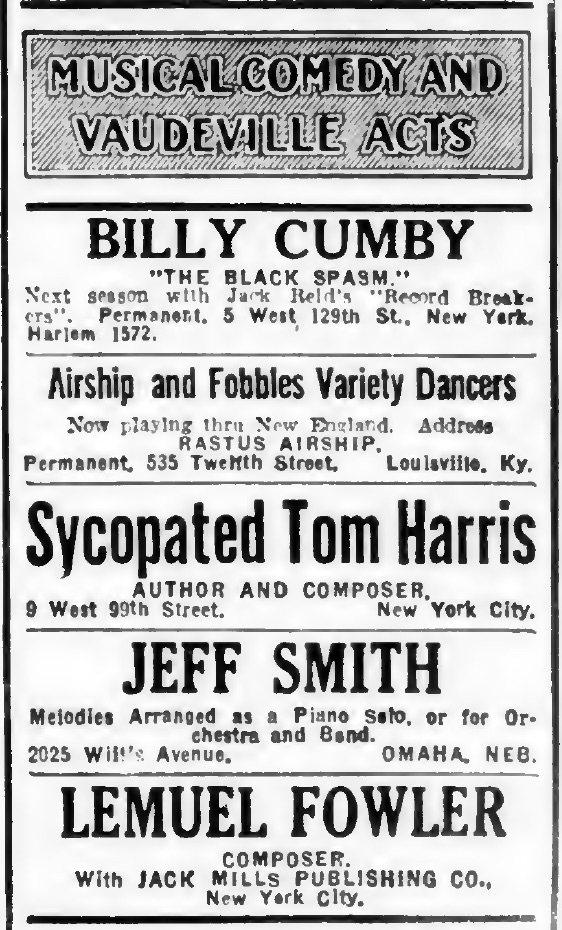

Billboard, June 30, 1923, p. 53 |

Fowler ran the ad shown above in Billboard on Oct. 6, 1923, Oct. 13, Oct. 20, Oct. 27, and finally on November 3. It appears to have cost $1 for each insertion. Note that by October, he no longer mentions the staff position at Jack Mills. |

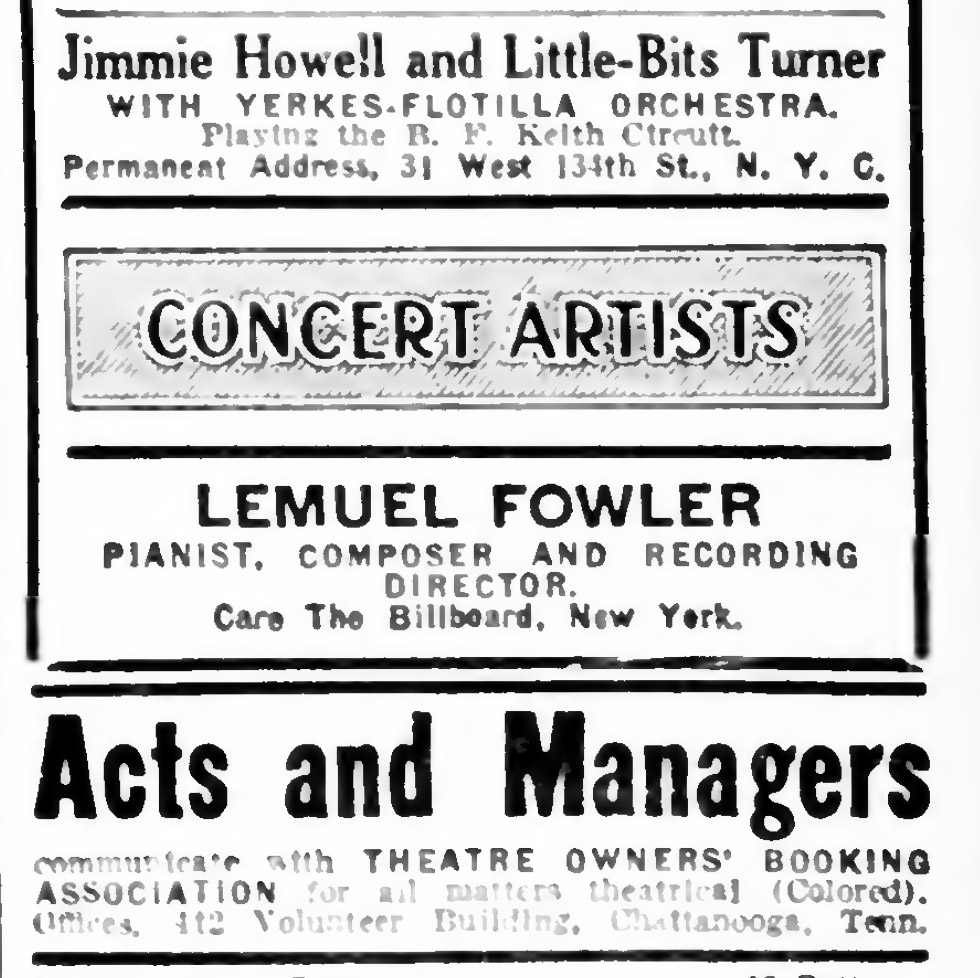

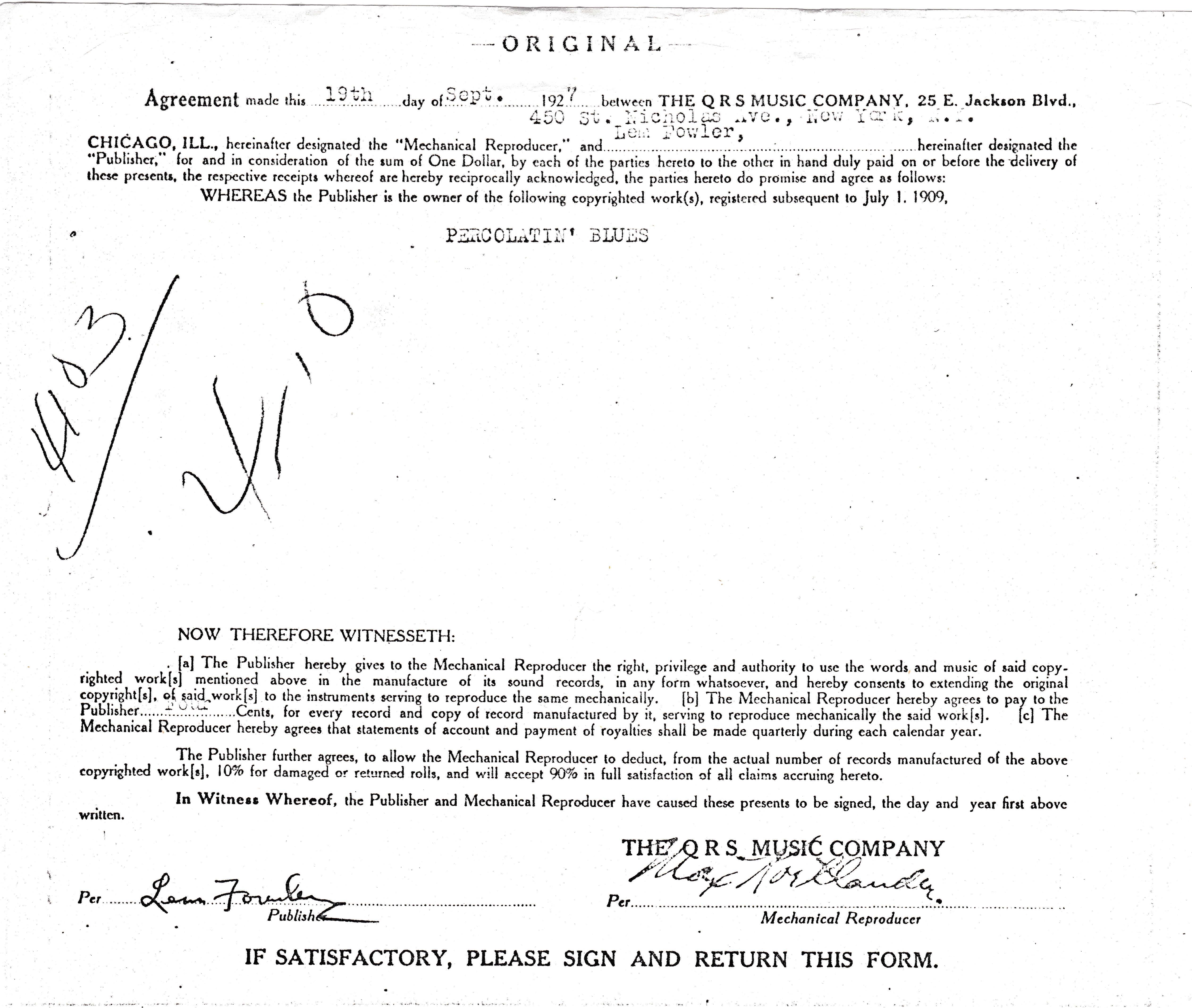

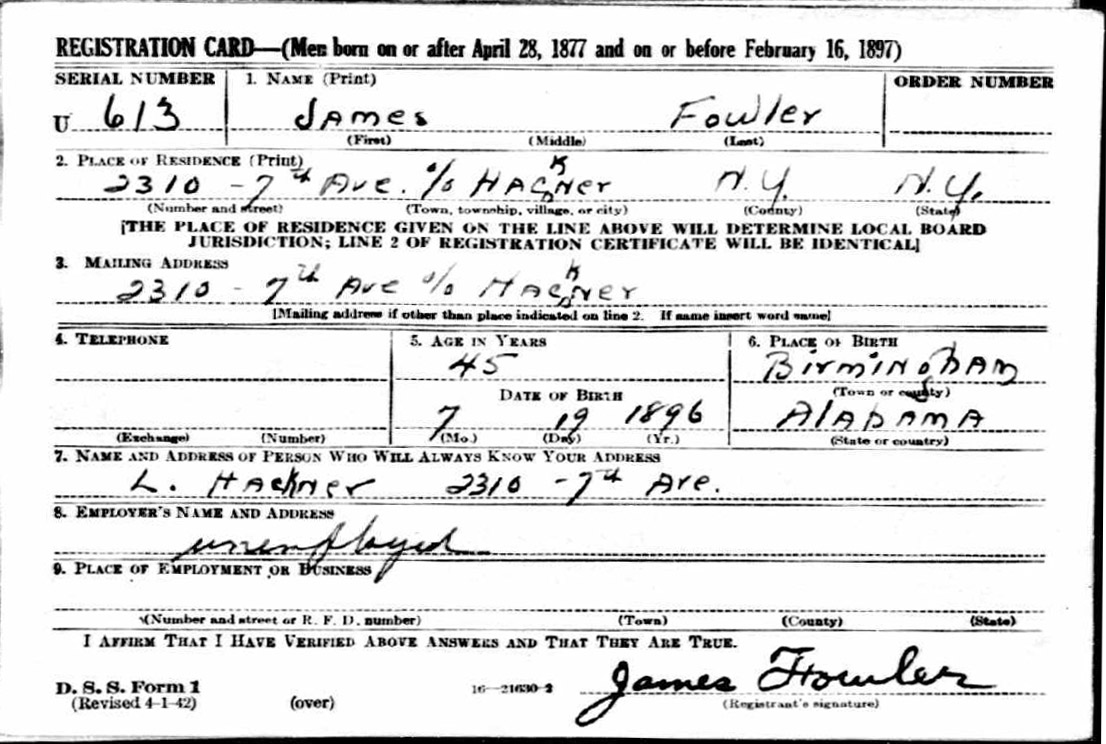

Fowler signature collage. At top, Lemuel James Fowler signature on "Marcelina" copyright application, 1920; at top left, stencil signature on QRS "Satisfied Blues" roll leader, 1923; second down on left, signature on Fowler/QRS contract for mechanical rights to "Percolatin' Blues", September 1927; third down on left, "Lem Fowler" stencil signature on QRS "Percolatin' Blues" roll leader, presumably also dating from September 1927; bottom left, signature on court document, 1922, courtesy researcher Chris Barry; top right center, "James Fowler" signature on WWII draft registration, 1942. Directly below the "James" are three "James" from "Relphow James" signatures on "Stomp 'Em Down" copyright application, 1925.

Note the very consistent capital "L" in all five of the "Lem" or "Lemuel" examples, and the variations in how the capital "F" is formed. The simpler way of rendering the capital "F" is characteristic of the many copyright registration specimens (not shown here).

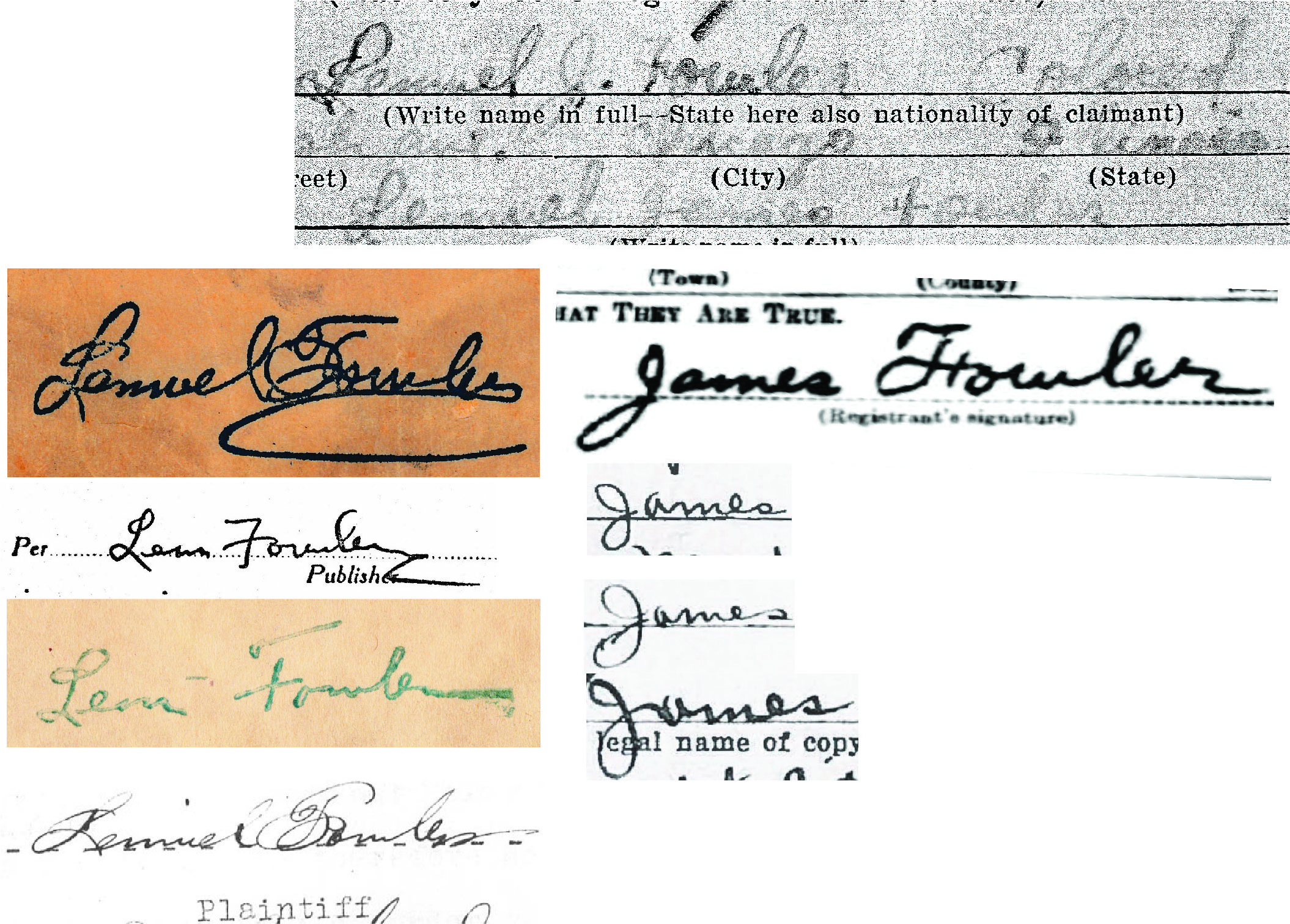

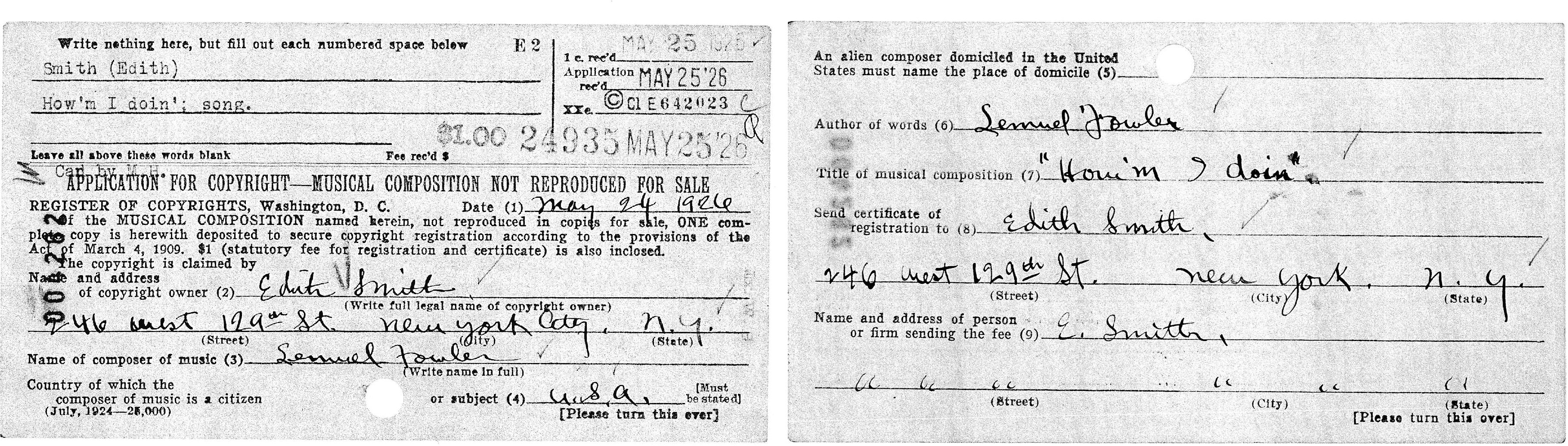

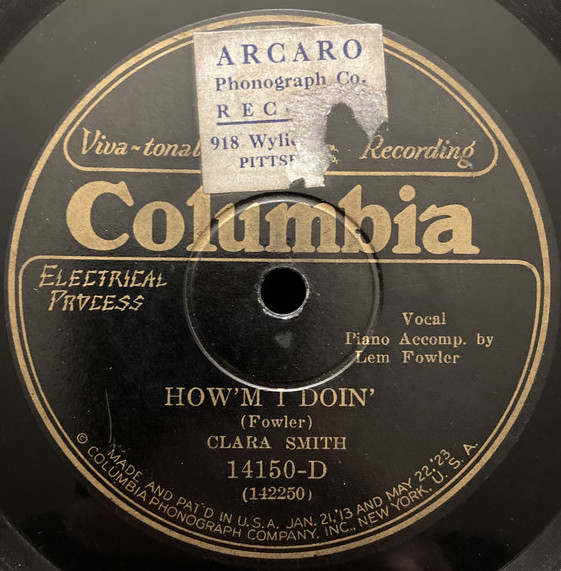

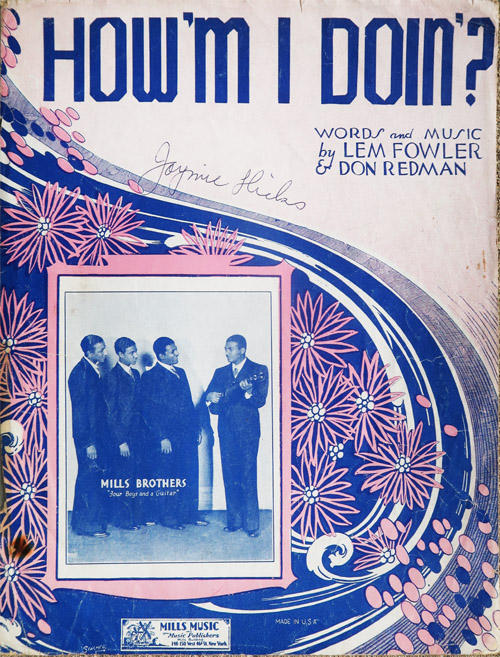

How'm I Doin', original copyright deposition and application card, May 25, 1926

How'm I Doin'" was recorded by Clara Smith with Fowler accompanying on the same day the copyright registration was received in Washington (May 25, 1926), as though it were a slow blues, rather than as a pop tune with a sixteen-bar verse and a sixteen-bar chorus.

|

|

|

|

pbc LF label.jpg)

|

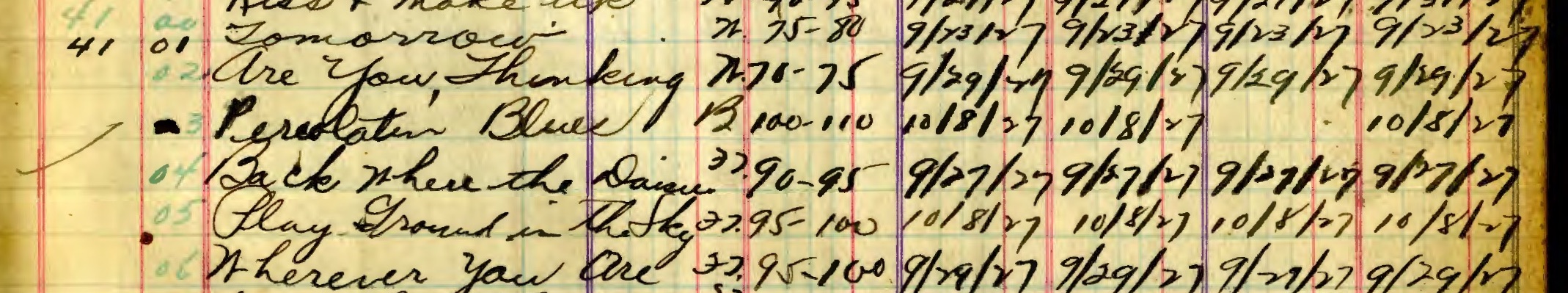

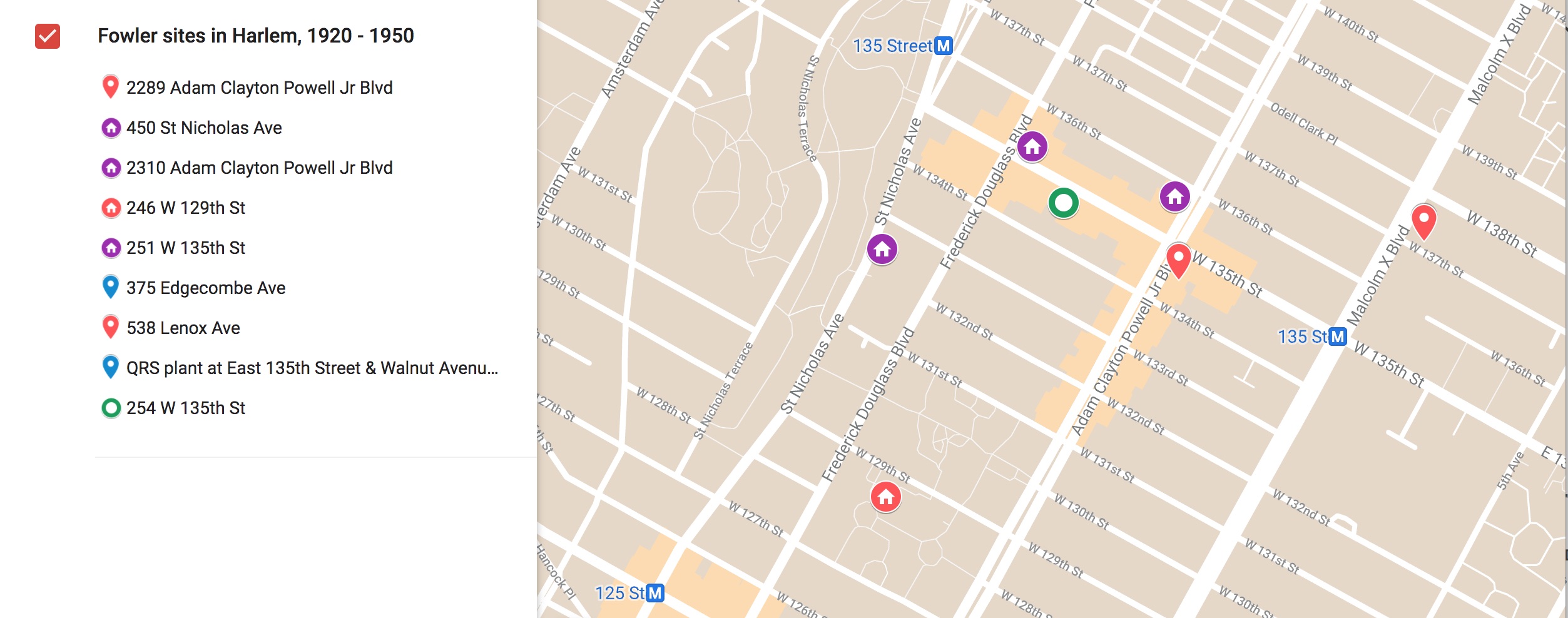

Documentation of each stage of production of QRS 4103, Percolatin' Blues. The contract (from Mike Montgomery's collection) leads to the inference that Fowler visited the QRS plant in the Bronx to record the roll the same day the contract was signed, September 19, 1927. The excerpt from the QRS factory ledger shows that the layout of the roll was completed on October 8 and masters sent to the other factories the same day. Musical Trade Review of November 26 (page 22) shows that the roll was listed as a December release, in agreement with the "1227" date on the roll label. Making the master was complete in a little less than three weeks after the recording; production and distribution took a couple of months. |

|

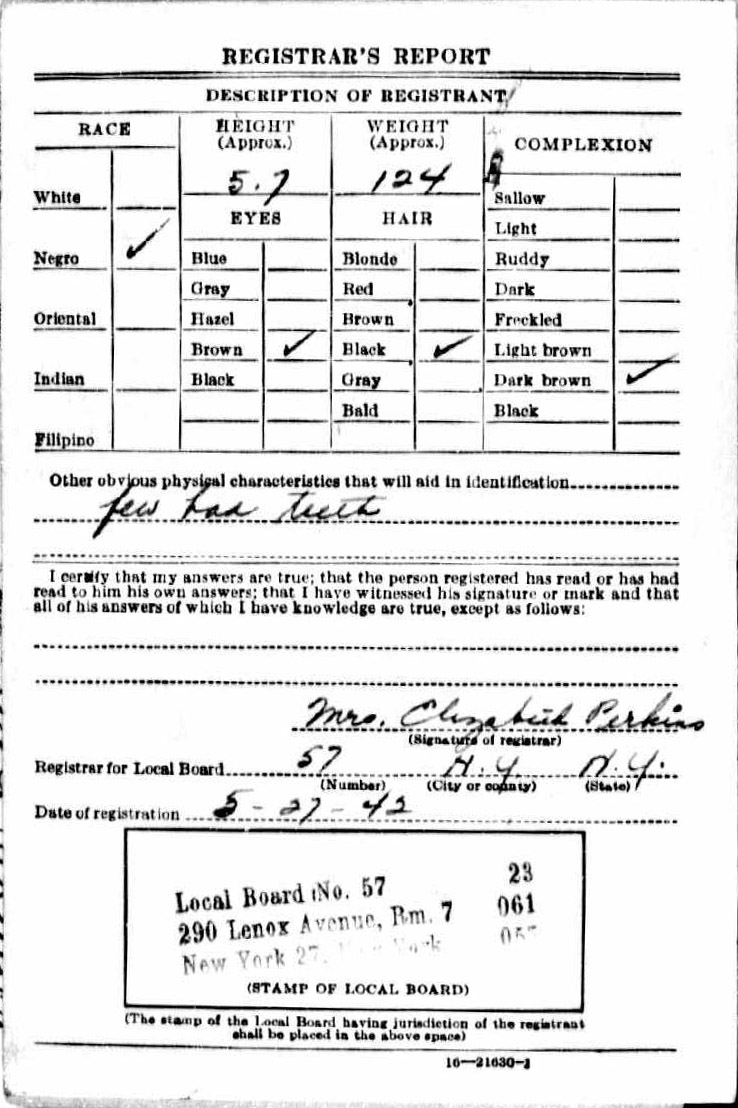

Sites in a few block area of Harlem associated with Lem Fowler, 1922-1950

2289 7th Avenue: office of Black Swan Records 1921-2, W.L. Albury Music Publishing 1922 Fowler used this as address for copyright registrations in 1922

538 Lenox Avenue: Dixie Music Shop, 1920 - c. 1926, used for copyright registrations in Fowler's name, Edith Smith's name, and in one case for "James Meller", from 1923 through early March 1925. Hughie Woolford, friendly competitor of Eubie Blake's back in Baltimore, lived in one of the apartments in the building for many years.

450 St. Nicholas Avenue: best documented home of Fowler's, in which he shows up as "James Fowler, musician" married to "Edith Fowler, housewife" in June 1925 in the NY State Census, and uses for copyright registrations from July 1925 through March 1929, and on the QRS contract for mechanical rights to "Percolatin' Blues" September 1927. Copyrights in the names Lemuel Fowler and "Relphow James" are sent to this address.

246 W 129th St (Apt. 64): Apparently the home of Edith Smith. Copyrights of which she is the owner are sent to this address starting in late March 1925, which continues through mid-1927.

254 W 135th St: Fowler plays his last documented live gig on Feb. 13, 1930 at a gathering of the South Carolina State College Club of NY, at "Unique Colony Circle", according to the NY Age, Feb. 22, 1930, p. 2.

2310 7th Avenue: site of Louis Hackner's "Colonial Tailoring" shop, which "James Fowler" gives as his c/o address on his WWII Draft Registration, 1942.

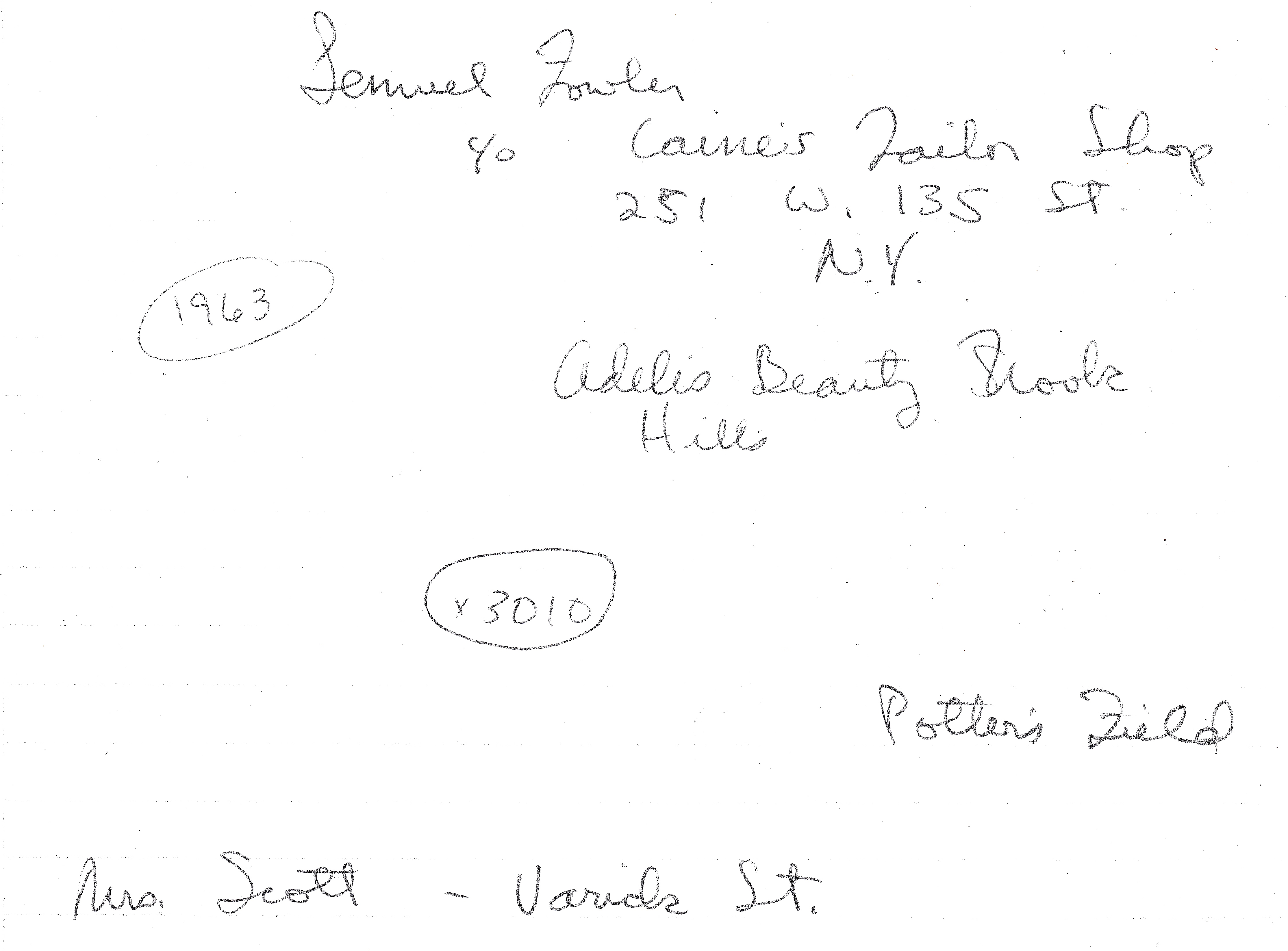

241 W 135th St: Almost across the street from the site of the 1930 gig, this was George Caines's tailor shop that Montgomery learned from ASCAP was the address to which Fowler's royalty checks were being sent, circa 1963-4. Also the address given by Fowler on the renewal of "He May Be Your Man" in 1950.

E 135th St and Walnut Ave, The Bronx: Location of the QRS factory in The Bronx where Fowler went to record his QRS rolls in the 1920s, and where he visited J. Lawrence Cook for a loan in about 1962. [Off map to the right and below.]

Google map of Lem Fowler's Harlem (20220120)

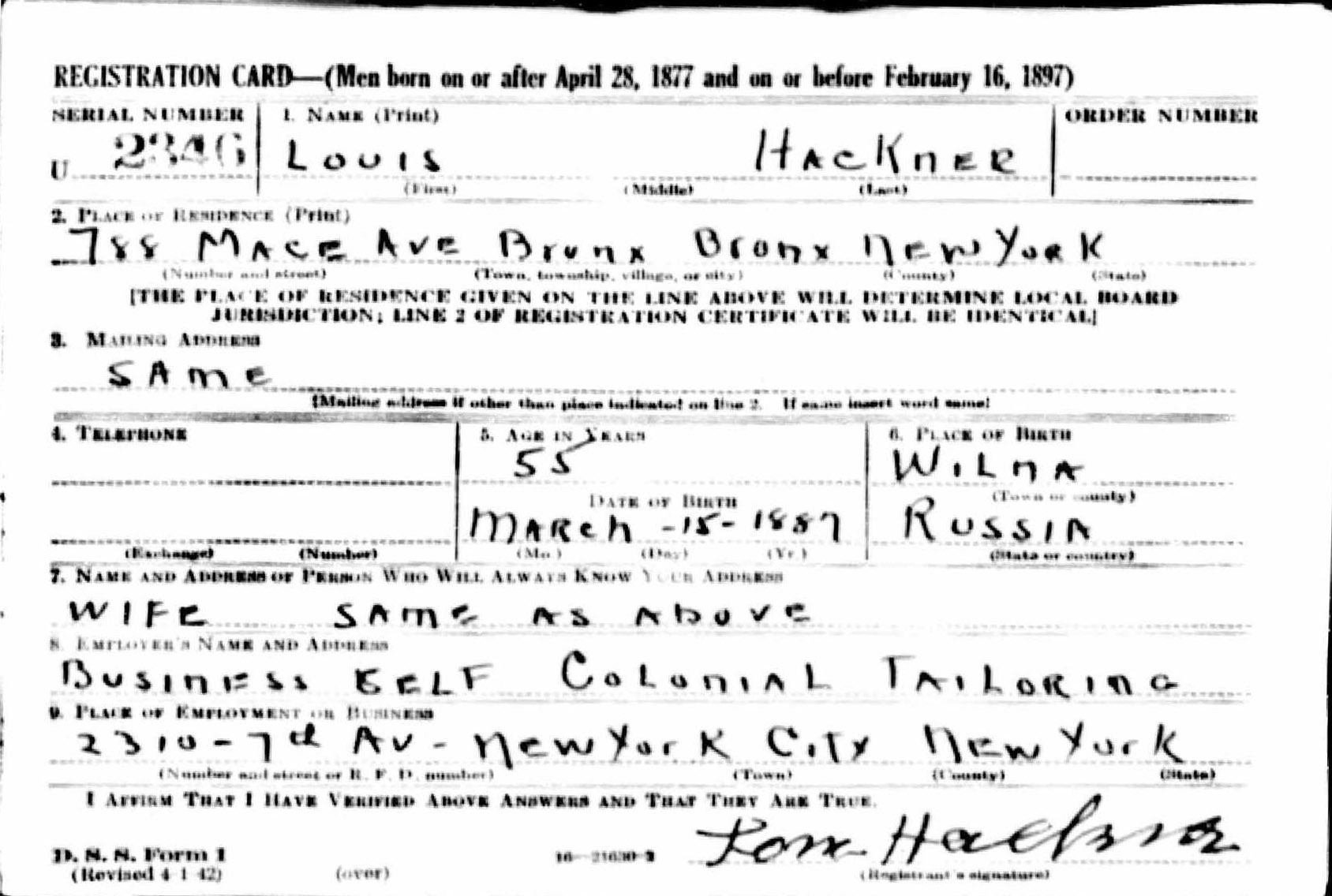

LOUIS HACKNER, Fowler confidant circa 1942

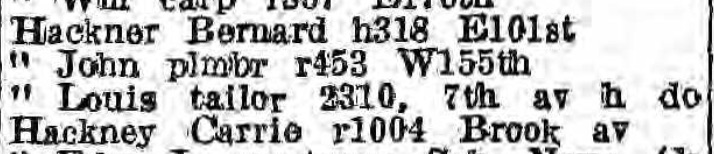

Louis Hackner, tailor, at 2310 7th Avenue in 1925 NY city directory

Hackner's WWII draft registration, April 26, 1942 in his home borough of the Bronx.

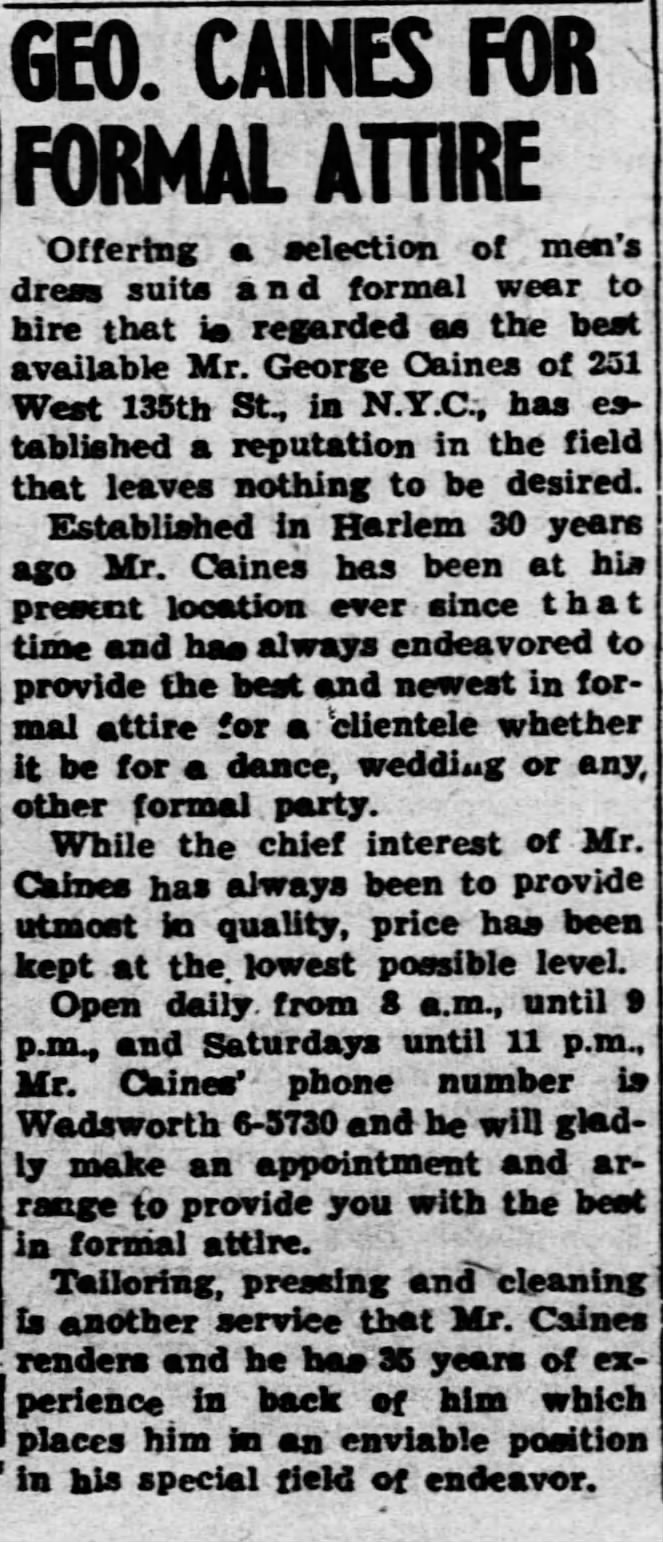

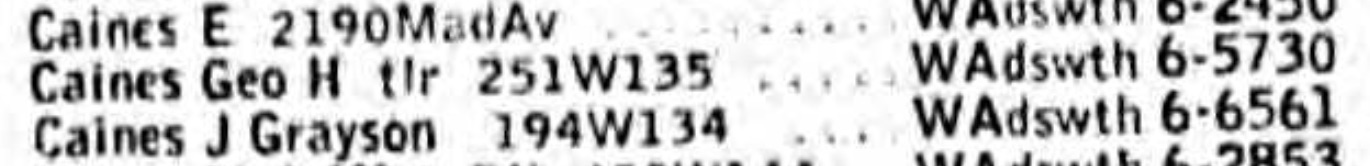

GEORGE HAMILTON CAINES, Fowler mailing address and friend in late 1940s and 1950s

George Hamilton Caines was born in Basseterre, St. Kitts, British West Indies on August 16, 1884, according to his WWI draft registration, as an alien resident, and on his application for naturalization, granted January 20, 1920. He had emigrated to the US in 1900. In the late teens and in 1920 he was working as a 'ship caulker' at a dry dock in Jersey City, while living at 141 W 135th St in Harlem. He married Minnie Bright, born April 24, 1895 in Virginia, on April 2, 1917.

In the 1920 census, Minnie was listed as a dressmaker. By the 1925 NY State Census, George has become a tailor, while Minnie is listed as a housewife. His shop at 251 W 135th St evidently opened in the early 1920s, first as "Brambill & Caines", apparently co-owned by George A. Brambill (c. 1872 - 1953, an interesting figure in his own right, but would take us pretty far afield from Lemuel Fowler to go into in more detail here) in the 1922 and 1925 city directories, subsequently as Caines's alone.

|

By 1964, when Mike Montgomery went to look for the shop to inquire about Fowler, the shop had been gone for some years. Mike sent a letter to Caines's home address on February 26, 1964, 375 Edgecombe Avenue, but he never received a reply.  George Caines died in November 1967, according to the Social Security Death Database. |

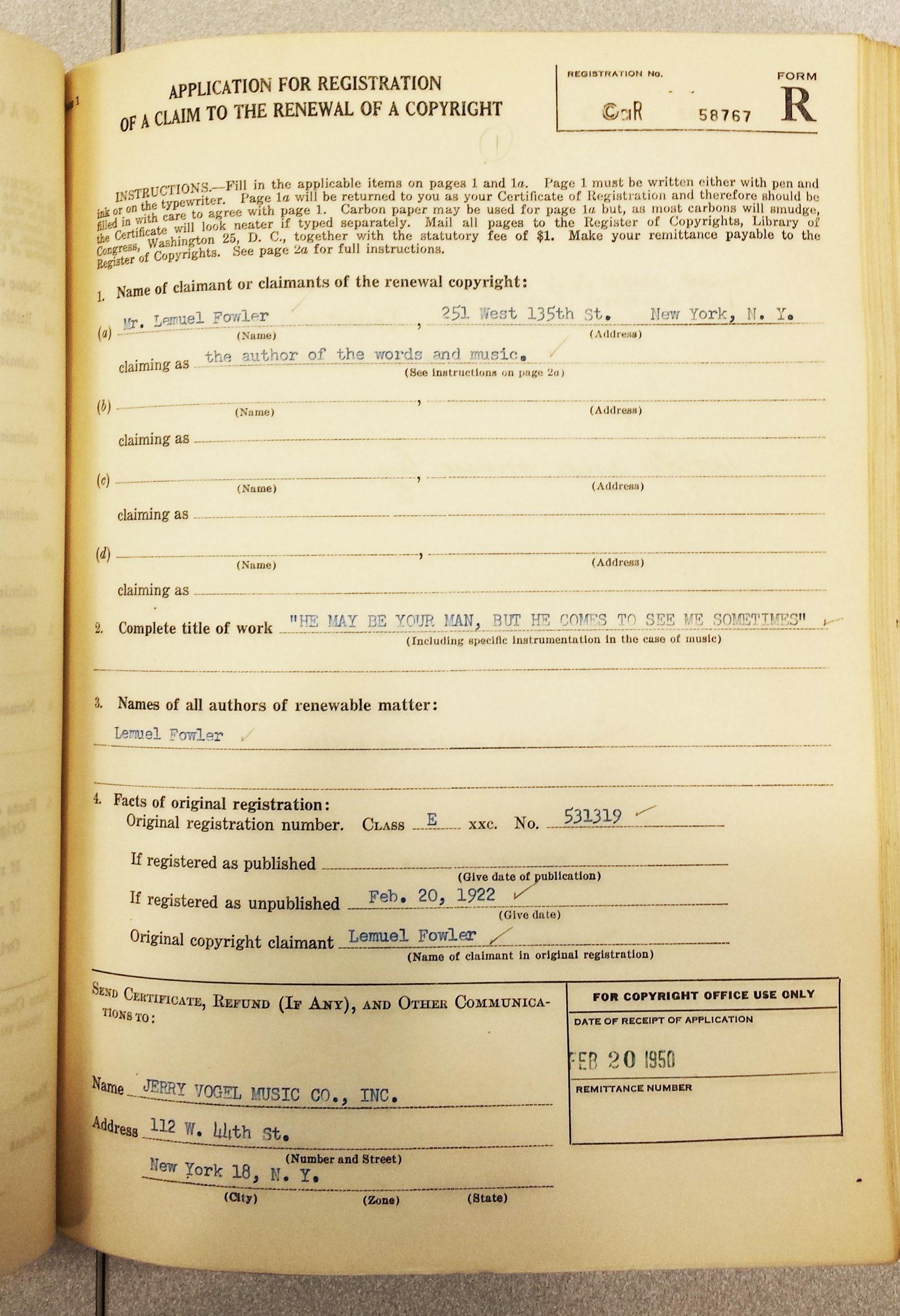

Renewal application in the Copyright Ledger for the earliest copyright of "He May Be Your Man", February 20, 1950, in which Fowler gives the address of Caines's tailor shop at 251 W. 135th Street as his. The copyright, probably Fowler's most valuable (perhaps along with "How'm I Doin'"), was assigned to Jerry Vogel Music Co.

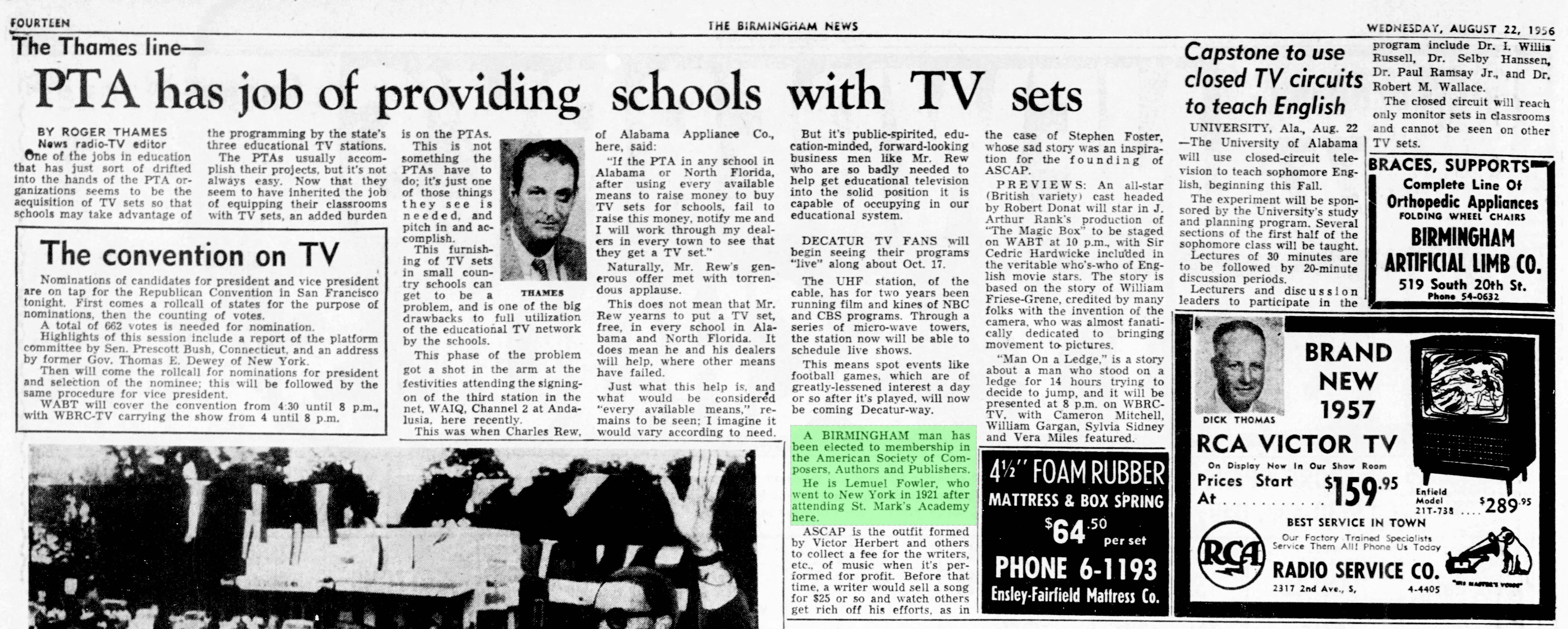

When I made the connection between the "James Fowler" in the WWII Draft Registration and the musician Lemuel James Fowler, I discussed this with New Zealand piano roll expert and historian Robert Perry, who immediately agreed with my handwriting analysis that tied that draft registration with the QRS stencil signature, which was the only Fowler signature we had available for comparison at the time. In recent years, Rob has followed up on this by researching Fowler's relatives in Birmingham. In the process, he came across the item in the main Birmingham newspaper, "The Birmingham News", from August 22, 1956 on page 14 in which the Times's media writer, Roger Thames mentions that a Birmingham native, Lemuel Fowler, has been elected to ASCAP, and that Fowler had gone to New York in 1921. The stay in Chicago is not mentioned. Thames also mentions that Fowler had attended St. Mark's Academy in Birmingham.

It seems that the only plausible way that Thames could have known this is via a communication from Fowler, or maybe a little less likely, from one of his surviving siblings. Perhaps Fowler was so proud of his election to ASCAP that he thought to inform his hometown newspaper.

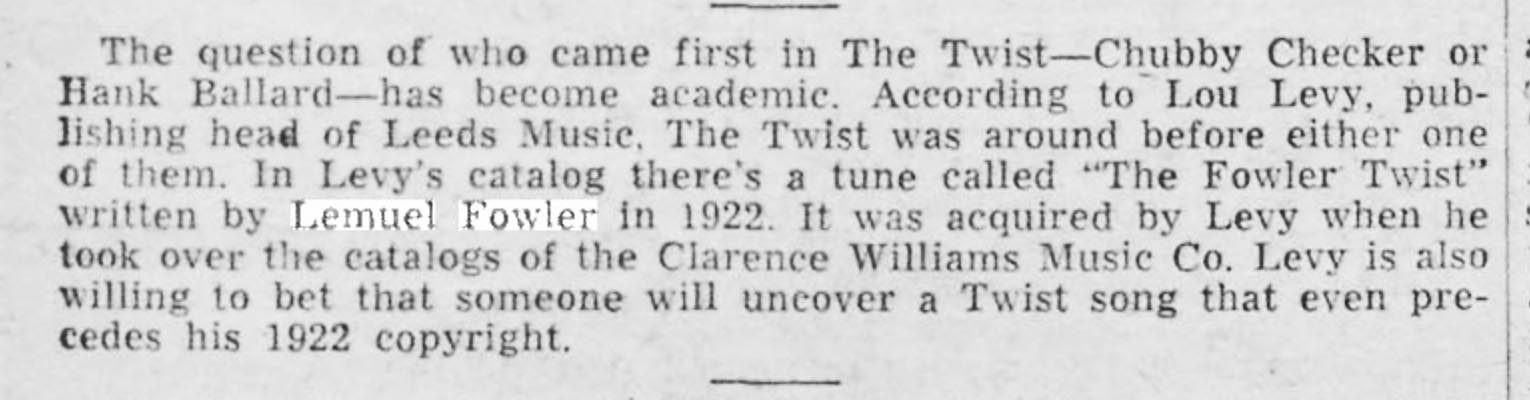

Another remarkable reference to Fowler appeared in Variety on December 20, 1961 (p. 43). The music publisher Leeds Music had acquired the catalog of Clarence Williams Music Co., which had in turn acquired the W.L. Albury publications "Fowler Twist" and "Ain't Got Nothing (Blues)" when the latter had folded in about 1923, and the manager of the publishing house noted the presence of "The Fowler Twist" in the Clarence Williams catalog that his organization now controlled.

There were many articles appearing in the early 1960s making the same point - that "The Twist" dated back to the 1920s, but no earlier article that I have found cites "The Fowler Twist", which, despite Lou Levy's hunch reported in the Variety item, may be the oldest such 'Twist' tune published. For example, an article in the Minneapolis Morning Tribune of March 12, 1962 on p. 24 cites "Mexican Twist" by the Castilian Serenaders, 1924, "Harlem Twist", 1928 (several bands), "Turtle Twist", by Jelly Roll Morton, 1929 - perhaps the best known of these today - "Texas Twist", 1930 and Gene Gifford's "New Orleans Twist" from 1935.

Evidently the singer Patti Page's (1927-2013) publicity people released a tidbit to the press in early 1962, which in both The Atlanta Constitution (Jan. 22, 1962, p. 33) and The Sandusky [OH] Register (Jan. 23, 1962, p. 16) read as follows: "What's so new about the Twist? In scanning the research files for her next Mercury record release, 'Let's Do the Twist,' Patti Page discovered that in 1926 [sic] a man by the name of Len Fowler [sic] wrote 'The Fowler Twist.'" Interestingly, perhaps Patti Page was more likely to notice such an entry in a file, because her birth name was Clara Ann Fowler! The fact that this item gets the first name and the date wrong seems to imply independent discovery from the articles that were based on the Variety item of Dec. 20, 1961.

One wonders whether Lemuel Fowler in his self-imposed obscurity in New York heard about the rediscovery of his 1922 tune in the context of the popularity of "The Twist". It was just around this time that Fowler reappeared at the QRS plant in the Bronx. We reproduce the relevant bit of the interview Mike Montgomery recorded with J. Lawrence Cook, printed in the Billings Rollography vol. 5. Montgomery is going over an alphabetized list of every name that appeared as the recording artist on hand-played QRS rolls with Cook, in an effort to elicit memories of these individuals. It is 1963 (the exact date is not given), and Cook gets to Fowler's name on Montgomery's list:

"COOK: Lem Fowler. So far as I know he is still living. He was over to the place last year. And we thought he was a ghost. We thought he was long dead, you know. And all of a sudden we looked up and I batted my eyes. And I said, "Lem, you're dead." He did a lot of the blues-type things. In fact, he still owes me the $2 he was supposed to bring me back the next week.

MONTGOMERY: Where does he live?

COOK: I don't know. But we were so surprised. We thought he was long gone. We knew he was so careless with his health, but he didn't look bad at all. He showed his age quite a bit. He didn't say where he was living. As a matter of fact, I expected him back. He borrowed $2 or $3, and said, "I'll show you; I've got my check coming in from some song or something next week..." This was 1962. We all thought he was long dead because we hadn't seen him in so long. So far as I know, Lem is still living.

MONTGOMERY: Would ASCAP know where he's living?

COOK: Yes. They would have his name and address.

MONTGOMERY: I want to talk to him!"

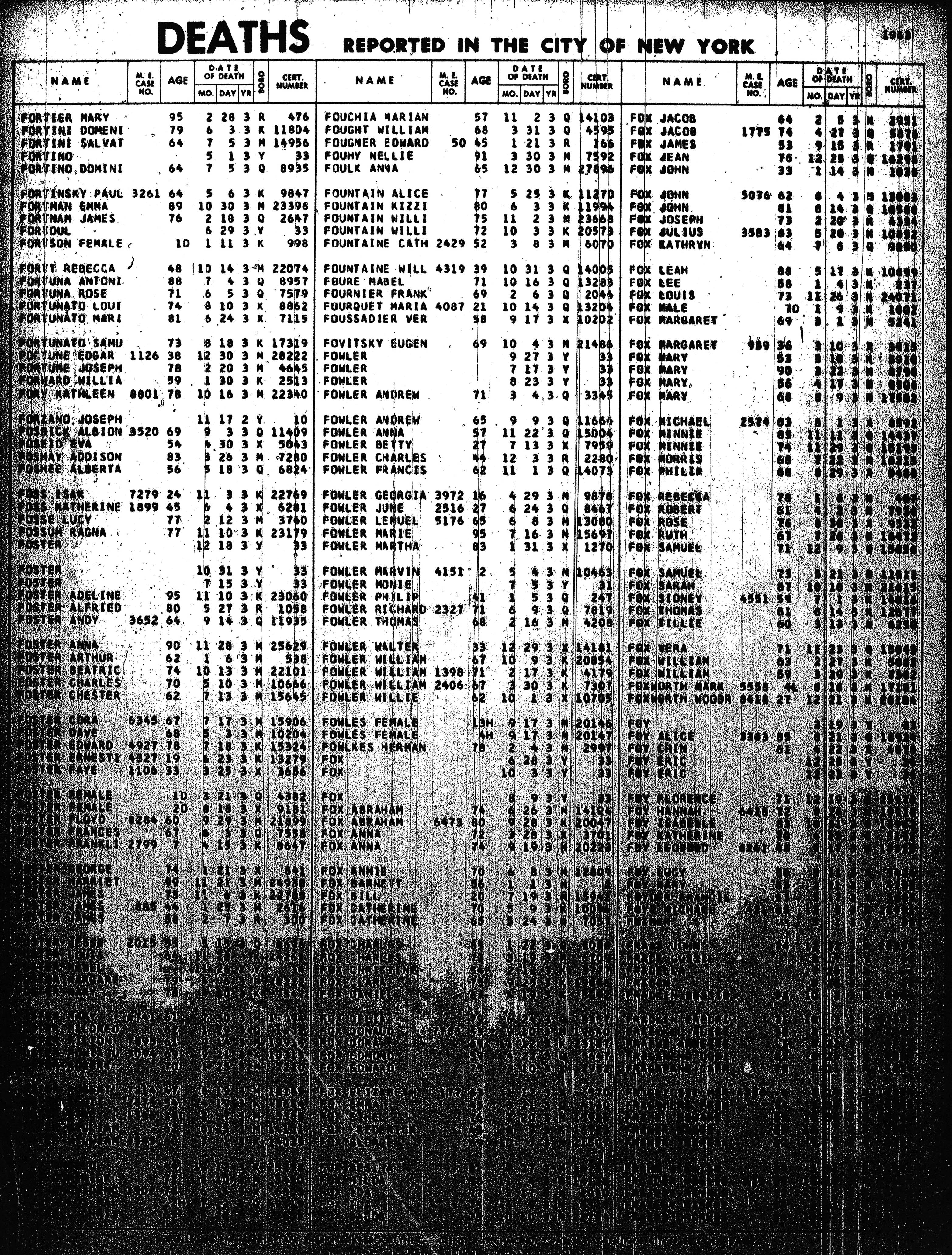

Death record listing, reproduced from microfilm copy at Mormon Family History Center, San Diego, November 20, 2013. On July 6, 2017, Ancestry.com published scans of these records to their online offerings. This documents Lemuel Fowler's death in Manhattan on June 8, 1963.

Because Fowler died in New York City, present policies of the City of New York do not permit anyone to examine the death certificate for post-1948 deaths, though the difference between the policies on this between the City of New York and the rest of the state of New York are the topic of current litigation at this writing. (Had Fowler died in the state of New York outside the city, his death certificate would been a public document after 2013.) See www.reclaimtherecords.org/records-request/24/.

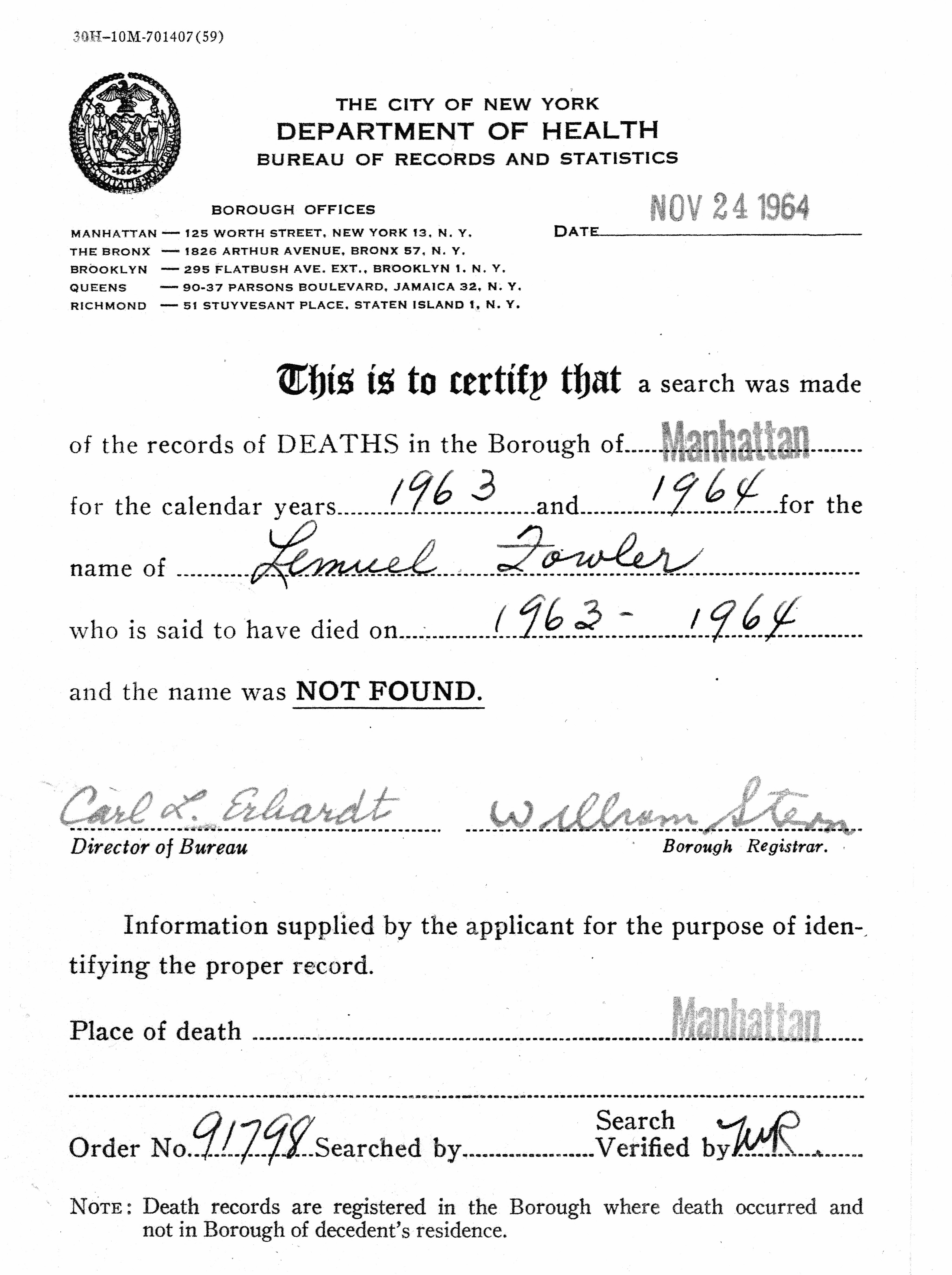

Mike Montgomery had had a search instituted of NY city death records in 1964 as part of his extensive search beginning in February of that year undertaken to learn of Fowler's fate since his visit to the QRS plant in the Bronx in 1961 or 1962. Unfortunately, somehow the office of the Dept. of Health failed to find the death record, as documented in what they sent back to Mike:

Mike Montgomery's quest for the elusive Lem Fowler did not end in his lifetime. In his final word on the topic, the excellent CD jewel case booklet he wrote for the RST Records CD JPCD-1520-2 "Lem Fowler: Complete Recorded Works 1923-1927 In Chronological Order", Mike concluded with:

"Lem must have wanted to remain an obscure figure. If he was alive in 1961 he must have been aware of the revived interest in jazz and blues music of the 1920s, the reissued recordings and the appearance of revival jazz bands. All he would have had to do was approach just about any jazz scholar, identify himself, and receive a red carpet treatment. But it didn't happen, unfortunately. . . .

I guess in lieu of knowing anything personal about Lemuel Fowler, we'll just have to be satisfied with the great, lively music he left behind.

Michael Montgomery, Detroit, Michigan, 1995"

Montgomery passed away June 22, 2011; a few months later I found the "James Fowler" 1942 Draft Card that connected back to Birmingham and the final resolution of some of the mysteries surrounding Lem Fowler. We still have no insight into the final mystery Mike pointed out: why did he choose to remain in that self-imposed obscurity at the end of his life? Perhaps the ongoing research will eventually provide some clues.

Robert I. Pinsker, San Diego, CA, January 2022